First: What Is a Ball Mill? A Quick Primer

Now, let’s turn to the core question: how does a ball mill work in practice? The process boils down to three interconnected stages—feeding, grinding, and discharging—each with distinct mechanisms that ensure efficient particle reduction.

How Does a Ball Mill Work? The 3 Core Operational Stages

Stage 1: Feeding – Introducing Material to the Mill

Feed Entry: Raw material (often in lump or granular form, 10–50 mm in size) is fed into the ball mill through a hollow trunnion—a cylindrical shaft at one end of the rotating shell. For wet grinding, water, oil, or a chemical slurry is added alongside the feed to lubricate the material, prevent dust, and aid in discharging fine particles.

Feed Control: Most industrial ball mills use a feeder (e.g., a vibrating feeder or screw feeder) to regulate the feed rate. Too much feed overwhelms the mill, leading to uneven grinding; too little wastes energy by letting grinding media collide with each other instead of the material.

Stage 2: Grinding – The Heart of the Ball Mill’s Mechanism

Shell Rotation: The ball mill’s cylindrical shell is driven by a motor, gearbox, and pinion system. It rotates at a speed that’s 40–70% of the “critical speed”—the speed at which centrifugal force would pin the grinding media to the shell wall (preventing them from falling). This optimal speed ensures the media lift and fall in a controlled way.

Media Movement: As the shell turns, the grinding media (e.g., 20–100 mm steel balls) are lifted along the shell’s inner wall by centrifugal force and friction. When they reach a certain height (determined by the rotation speed), gravity overcomes centrifugal force, and the media cascade back down into the center of the shell.

- Material Breakdown: There are two ways the media grind the material:

Impact: When the heavy media fall, they strike the feed material with significant force, crushing large lumps into smaller particles.

Attrition: As the shell rotates, the media also slide and roll against each other and the shell’s inner liner. This rubbing action grinds the crushed particles into finer powders, smoothing out irregularities and ensuring a uniform particle size.

Liner Role: The shell’s inner liner (made of manganese steel, rubber, or ceramic) plays a key role here. It protects the shell from wear and can be designed with ribs or lifters to enhance media lifting—boosting impact force and grinding efficiency.

Stage 3: Discharging – Collecting the Finished Product

Overflow Discharge: The most common method (used in overflow ball mills). The discharge trunnion (at the opposite end of the feed) is positioned slightly lower than the shell’s centerline. As the shell rotates, the ground material and liquid (for wet grinding) overflow out of the trunnion by gravity. A screen may be used to catch oversized particles, which are recirculated back into the mill for further grinding.

Grid Discharge: Used in grid ball mills, this method features a grid at the discharge end. The grid has small openings that allow only fine particles to pass through, ensuring a more consistent product size. Oversized particles are retained in the mill until they’re small enough to exit.

Dry Discharge: For dry grinding, the finished powder is often carried out by a stream of air or gas, which also helps remove dust and cool the mill.

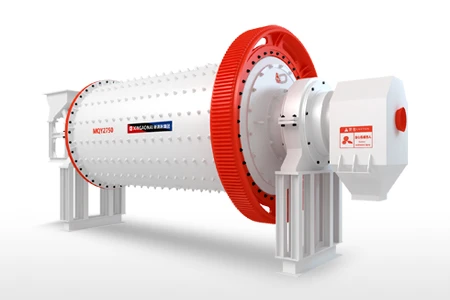

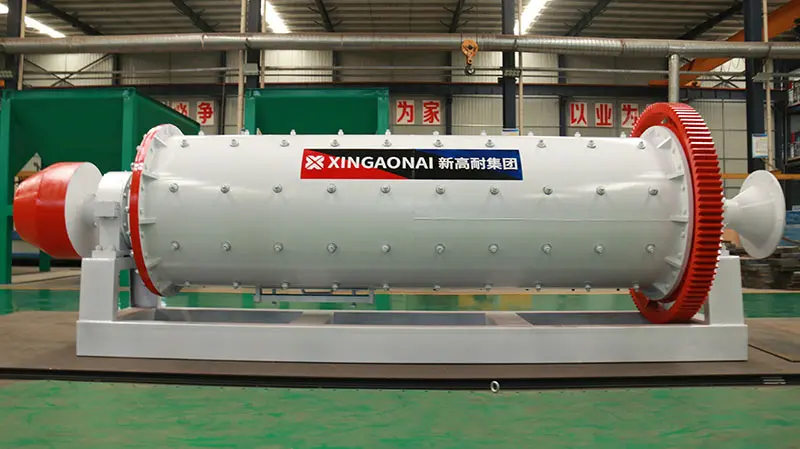

Key Components That Power a Ball Mill’s Operation

Cylindrical Shell: The main body that holds the media and feed. Its size (diameter and length) determines the mill’s capacity—larger shells handle more material but require more energy.

Grinding Media: The “tools” that do the grinding. Steel balls are used for hard materials (e.g., ores), while ceramic beads are preferred for contamination-free applications (e.g., pharmaceuticals). Media size is tailored to the feed—larger media crush coarse lumps, and smaller media grind fine particles.

Trunnions: Hollow shafts that support the shell and enable feeding/discharging. They rest on bearings to reduce friction during rotation.

Drive System: Motor, gearbox, and pinion that control the shell’s rotation speed. Variable-speed drives are common today, allowing operators to adjust speed for different materials.

Liner: As mentioned earlier, this wear-resistant layer protects the shell and optimizes media movement. Rubber liners are quieter and gentler (good for wet grinding), while steel liners are durable for hard feeds.

Factors That Influence How a Ball Mill Works (Efficiency Tips)

Rotation Speed: Too slow, and the media won’t lift high enough (poor impact); too fast, and media stick to the shell (no grinding). The optimal speed depends on the mill’s size and media type.

Media Load and Size: The media should fill 30–45% of the shell’s volume. A mix of media sizes (e.g., large and small balls) ensures both coarse crushing and fine grinding.

Feed Properties: Hard, dense materials require larger media and slower speeds; soft materials need smaller media and faster speeds. Feed size also matters—pre-crushing large lumps reduces the mill’s workload.

Wet vs. Dry Grinding: Wet grinding uses liquid to reduce friction and aid discharge, making it ideal for sticky materials. Dry grinding is better for heat-sensitive materials but generates more dust.